At the end of every year major dictionary compilers choose their ‘Word of the Year’. This doesn’t have to be a novelty word. It can be an old word that has made a comeback or taken on a new meaning, such as the pronoun “they”. The Merriam Webster dictionary famously announced “they” as their Word of 2019 after it became a popular way of referring to people with non-binary gender identities (“Meet my friend. They are a lawyer.”). According to Merriam Webster, “they” saw a surge in lookups in 2019 .

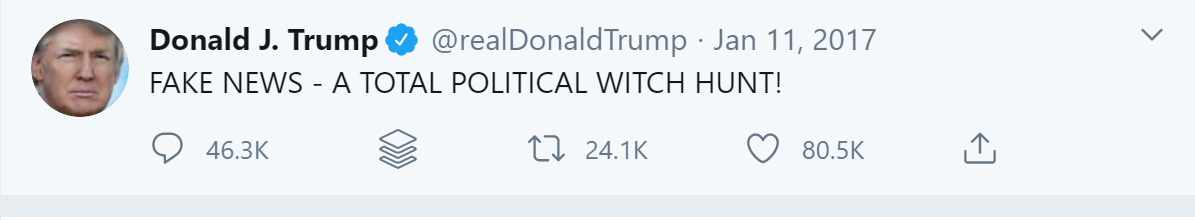

For other dictionary compilers, however, the Word of the Year is not necessarily the entry that was most looked up. Rather, it’s a word of social or cultural significance that captures the spirit of the year gone by. Based on that criterion, the Oxford Dictionaries opted for “climate emergency” as the Word of 2019. Interestingly, the runner-ups (other words that were shortlisted) are all related to the environment, such as “climate denial,” “eco-anxiety,” “extinction” and “flight shame” reflecting the mood of the year in which Greta Thunberg embarked on her crusade to raise global awareness of climate change. For similar reasons, in 2017, the year marked by malicious misinformation and plagued by pernicious propaganda, the Collins Dictionary named “fake news” as their Word of the Year.

Although it has just begun, the mood and spirit of 2020 can largely be summarised in one word: Coronavirus. Having consulted major online dictionaries – Cambridge, Oxford, Macmillan – I was surprised to find that the word is already there. Has it always been there or is it a new addition?

The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary even provided the following example, which seems eerily prescient; unless it has been updated very recently:

Precautions were taken to try to limit the spread of coronavirus.

A look up in the Macmillan Dictionary suggests that online dictionaries are indeed updated more frequently than I believed. Their example accompanying the entry is:

On 9 January 2020, China reported a novel coronavirus as the causative agent of this outbreak.

Extensive media coverage of the coronavirus has brought to the fore some interesting words and phrases (I’ve bolded them in what follows). Like “coronavirus” they probably have been out there but have started to occur with higher than usual frequency, for example flatten the curve – an attempt to mitigate the outbreak by reducing the number of new infections. Of course, the best way to achieve that is by social distancing or, in plain terms, staying away from other humans, and, if you have been in contact with an infected individual, through self-isolation or home quarantine. “Quarantine” – a word of Latin/Italian origin related to a period of 40 (not 14!) days all ships coming into Venice had to be isolated in order to prevent the spread of the plague in the Middle Ages – is worthy of its own article and will not be discussed here. Let’s, however, look instead at unprecedented.

Photo by Nathan Smith on Flickr under a Creative Commons License [CC BY-ND 2.0]

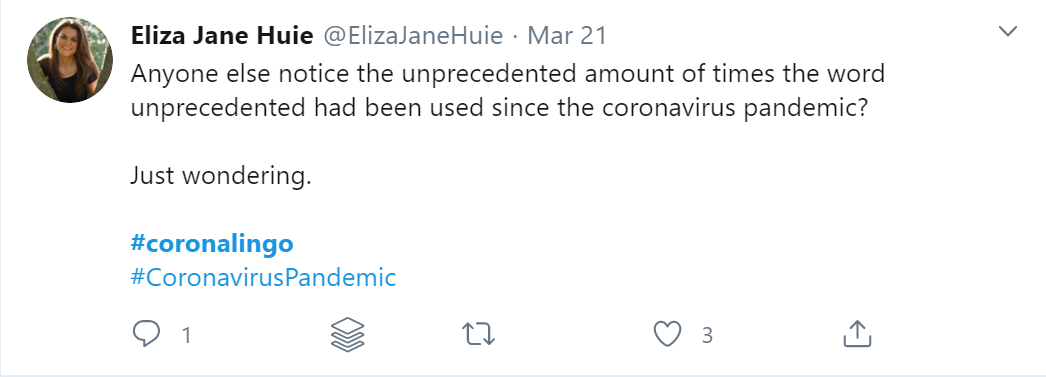

An “unprecedented rise in the number of cases”, “unprecedented time for health workers”, “countries entering unprecedented lockdowns” – all this is just from a quick scan of the news stories from the past few days. Apparently, I’m not the only one who noticed a sudden surge in the popularity of the word, as can be see from this tweet:

(The teacher in me says it should be “number of times”, not amount, but I’m probably being too pedantic.)

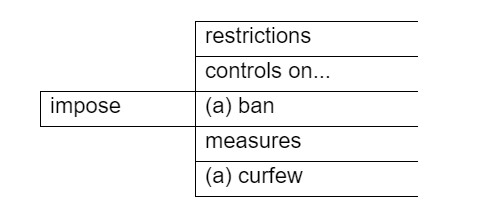

Among the verbs that seem to be ‘trending’ in these anxiety inducing times are curb and impose – both useful for academic writing. The former has been cropping up a lot lately as part of the following chunks: curb the spread of the coronavirus or curb the outbreak; but also in curb socializing / movement / the financial impact (of the outbreak). The latter is also useful for students because it is one of 570 words in the Academic Word List (AWL). According to the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), it often occurs with the following collocations presented here in a collocation fork:

I’m sure you have come across most of these in the past few days.

Let’s look at some more examples in context:

- “To put a ring around cities of this size and population is unprecedented” – a quote in NY Times, January 20, 2020

- France imposed a draconian lockdown unseen during peacetime – Aljazeera, March 18, 2020

- How countries from China to Italy have imposed measures to curb the spread of Covid-19 – The Guardian, March 18, 2020

Of course, as we know, the groups who are particularly vulnerable to the virus are the elderly and people with pre-existing health … .

That’s right. This word combination, together with underlying health problems / conditions, has become such a staple feature of Corona-speak that you immediately recalled the last word in the sequence. This is a result of what is known as lexical priming, when repeated exposures (to a large extent in the media) to certain strings of words lead you to expect (=primes you) to hear or see these words together.

Turning now to the field of education, we have also witnessed a slew of buzzwords in the wake of the outbreak. Suddenly breakout rooms and screencasting are the talk of the town.

This is as a result of teachers incorporating digital technology on an unprecedented… that’s right, scale! One term that I hear a lot is remote teaching. Interestingly, we don’t normally say “remote learning”; instead, “learning” and “education” prefer the company of “distance” – distance learning / distance education (again, according to COCA). I’d be happy to hear your thoughts on that.

Finally, the corona crisis has given rise to genuinely new words (neologisms), particularly portmanteau words, i.e. words produced by mashing two existing words. Some examples include:

covidiot (COVID-19 + idiot) = a person who ignores the rules of social distancing or hoards goods. (Which reminds me, we almost forgot to mention panic buying – another collocation that’s gone coronaviral).

Photo by Ben Schumin on Flickr under a Creative Commons License [CC BY-SA 2.0]

quarantini (quarantine + martini) = a drink you have at home while self-isolating (or socially distancing? I’m not sure anymore).

On this note, here’s to your health, and the hope that there’s a light at the end of this Coronatunnel.

Stay well, as we say these days,

Lexically yours,

Leo Selivan

I would like to thank Rakesh Bhanot, Tatiana Maslova, Daniel Portman, Tomasz Róg, Marlene Goldberg and others who contributed some of the above items in a Facebook discussion.

About Leo

About Leo

Leo Selivan began his career in ELT more than 15 years at the British Council in Tel Aviv, where, among other things, he was a content writer for the British Council & BBC website TeachingEnglish. Today, Leo is a freelance lecturer teaching courses in Second Language Acquisition, ELT methodology, Corpus Linguistics and Genre Analysis. He also travels extensively to give workshops, and mentor teachers and teacher trainers. His professional writing credits include Lexical Grammar (Cambridge University Press, 2018) and articles in Modern English Teacher, EFL Magazine, The Guardian Education, Humanising Language Teaching as well as his own aptly-named blog Leoxicon.

Contribute to the blog

If you are a member of IATEFL and would like to contribute to the blog, we’d love to hear from you at [email protected] or [email protected]. We’re looking for stories from our members, news about projects you’ve been involved in, and anything else you think those connected to English language teaching would be interested in reading. We look forward to hearing from you! If you’re not a member, why not join us?